Franois VILLON (1431- c1463)

Ballade de merci

Chartreux et a Celestins,

Mendans et a Devoctes,

A musars et clacque patins,

A servans et filles mignoctes

Portans seurcoz et justes coctes,

A cuidereaux d'amours transsiz

Chauans sans mehain fauves boctes,

Je crye a toutes gens mercys.

A fillectes moustrans tetins

Pour avoir plus largement hostes,

A ribleurs, menneurs de hutins,

A batelleurs trayans mermoctes,

A folz, folles, a sotz, a soctes,

Qui s'en vont cyfflant six a six

A vecyes et marlioctes,

Je crye a toutes gens mercys.

Synon aux tratres chiens matins

Qui m'ont fait ronger dures crostes,

Macher mains soirs et mains matins,

Que ores je ne crains troys croctes.

Je feisse pour eulx pez et roctes,

Je ne puis, car je suis assiz.

Auffort, pour esviter roctes,

Je crye a toutes gens mercys.

C'on leur froisse les quinze costes

De groz mailletz, fors et massiz,

De plombees et telz peloctes!

Je crye a toutes gens mercys.

The "Excuse Me" Ballade

To Clestnes and monks Carthus-

ian, Mendicants, and Elvis fans,

to dealers, dreamers, foxy flooz-

ies flaunting ass in tight short pants,

to ancient gigolos, who jog

in multicolored running shoes,

and cloppers in designer clogs,

I ask that they my sins excuse.

To acrobats with apes in tow,

to bikers looking for a brawl,

to tourists coming from a show:

whistling, six wide wall-to-wall.

To teenage pros who bare their boobs

and so entice the johns to call,

to tiny hipsters with tattoos,

I beg forgiveness of them all.

Except those vicious carrion birds

by whom I marbles shat and gnawed

on crusts for many an eve and dawn,

and whom I value not three turds.

For them I'd gladly make a fart,

but can't because I'm sitting down,

and just so they won't feel left out,

I cry excuse me everyone.

May men their fifteen ribs destroy

by mighty hammers swung with joy

and also by a wrecking ball:

I shout so sorry to them all.

其他几首法英对照

Ballade de la grosse Margot

Se j'aime et sers la belle de bon hait.

M'en devez-vous tenir ne vil ne sot ?

Elle a en soi des biens fin souhait.

Pour son amour ceins bouclier et passot ;

Quand viennent gens, je cours et happe un pot,

Au vin m'en vois, sans dmener grand bruit ;

Je leur tends eau, fromage, pain et fruit.

S'ils payent bien, je leur dis que " bien stat ;

Retournez ci, quand vous serez en ruit,

En ce bordeau o tenons notre tat. "

Mais adoncques il y a grand dhait

Quand sans argent s'en vient coucher Margot ;

Voir ne la puis, mon coeur mort la hait.

Sa robe prends, demi-ceint et surcot,

Si lui jure qu'il tendra pour l'cot.

Par les cts se prend cet Antchrist,

Crie et jure par la mort Jsus-Christ

Que non fera. Lors empoigne un clat ;

Dessus son nez lui en fais un crit,

En ce bordeau o tenons notre tat.

Puis paix se fait et me fait un gros pet,

Plus enfl qu'un velimeux escarbot.

Riant, m'assied son poing sur mon sommet,

" Go ! go ! " me dit, et me fiert le jambot.

Tous deux ivres, dormons comme un sabot.

Et au rveil, quand le ventre lui bruit,

Monte sur moi que ne gte son fruit.

Sous elle geins, plus qu'un ais me fais plat,

De paillarder tout elle me dtruit,

En ce bordeau o tenons notre tat.

Vente, grle, gle, j'ai mon pain cuit.

Ie suis paillard, la paillarde me suit.

Lequel vaut mieux ? Chacun bien s'entresuit.

L'un l'autre vaut ; c'est mau rat mau chat.

Ordure aimons, ordure nous assuit ;

Nous dfuyons honneur, il nous dfuit,

En ce bordeau o tenons notre tat.

Ballad of the fat Margot

If I love and serve the fine lass wholeheartedly,

shall you hold me for wicked or fool?

She possesses all the goods I could wish for.

I strap on shield and sword for her love's sake.

When people go in, I hurry to grab a mug

and fetch some wine without further ado.

I hand them water, cheese, bread and fruits.

Provided they pay well, I tell them "All is well,

come back here when you are horny,

in this brothel where we are established!"

Still at times there is much discontent

when Margot comes to sleep penniless.

I cannot stand her face, my heart burns with hatred.

I grab her dress, her belt and apron,

swearing I'll take them for payment.

She hugs her ribs and yells blue murder,

curses and swears by the name of the Christ

that she won't abide. So I grab a splinter of wood

and carve words upon her nose,

in this brothel where we are established.

Then peace is made, and she lets off a thick fart,

more swollen than a venomous dung beetle.

Then she bangs me square on the head, laughing,

talks merry and stroke my tigh.

Now we're both drunk, and sleep as logs.

As we wake up, her belly is gurgling,

she climbs on me not to waste her fruit.

I'm moaning beneath her, she flattens me like a plank.

Her fornication is the end of me,

in this brothel where we are established.

In times of gale, frost or hail, my bread gets always baked.

I am debauched, and she follows suit.

Which one is best? We are evenly matched.

Cat and mouse compete in laziness.

We relish in filth, so does filth surround us.

We flee honour, so does honour flee us,

in this brothel where we are established.

https://lyricstranslate.com

L'pitaphe de Villon ou " Ballade des pendus "

Frres humains, qui aprs nous vivez,

N'ayez les coeurs contre nous endurcis,

Car, si piti de nous pauvres avez,

Dieu en aura plus tt de vous mercis.

Vous nous voyez ci attachs, cinq, six :

Quant la chair, que trop avons nourrie,

Elle est pia dvore et pourrie,

Et nous, les os, devenons cendre et poudre.

De notre mal personne ne s'en rie ;

Mais priez Dieu que tous nous veuille absoudre !

Se frres vous clamons, pas n'en devez

Avoir ddain, quoique fmes occis

Par justice. Toutefois, vous savez

Que tous hommes n'ont pas bon sens rassis.

Excusez-nous, puisque sommes transis,

Envers le fils de la Vierge Marie,

Que sa grce ne soit pour nous tarie,

Nous prservant de l'infernale foudre.

Nous sommes morts, me ne nous harie,

Mais priez Dieu que tous nous veuille absoudre !

La pluie nous a dbus et lavs,

Et le soleil desschs et noircis.

Pies, corbeaux nous ont les yeux cavs,

Et arrach la barbe et les sourcils.

Jamais nul temps nous ne sommes assis

Puis , puis l, comme le vent varie,

A son plaisir sans cesser nous charrie,

Plus becquets d'oiseaux que ds coudre.

Ne soyez donc de notre confrrie ;

Mais priez Dieu que tous nous veuille absoudre !

Prince Jsus, qui sur tous a maistrie,

Garde qu'Enfer n'ait de nous seigneurie :

A lui n'ayons que faire ne que soudre.

Hommes, ici n'a point de moquerie ;

Mais priez Dieu que tous nous veuille absoudre !

绞刑犯谣曲

在我们之后存世的人类兄弟,

请不要对我们铁石心肠,

只要我们受到你们怜惜,

天主就会提前对你们恩赏。

你们看到我们五六个紧相傍:

我们的皮肉,曾保养得多鲜活

早就被吃光和烂掉剥落,

我们的骨头成了灰烬和齑粉。

没有人嘲笑我们的罪恶;

请祈求天主,让大家宽恕我们!

我们兄弟般呼喊你们,你们对此

不要不理,尽管我们被判上了法场

一命归阴。但你们深知

凡是人理智都要热狂;

请原谅我们,既然我们已死亡,

来到圣母玛利亚之子面前悔过,

但愿他的恩泽不要所剩不多,

让我们免受可怕雷霆的劈分。

我们已经离世,不受心灵折磨;

请祈求天主,让大家宽恕我们!

雨水将我们淋得湿透和冲洗,

晒干和晒黑我们的是太阳;

喜鹊、乌鸦啄去我们的眼珠子,

把胡须和眉毛也都拔光。

我们任何时候都在摇晃;

风向忽东忽西,随意变化交错,

不停地把我们吹得忽右忽左,

乌啄食我们就像戳顶针。

因此,不要加入我们一伙,

请祈求天主,让大家宽恕我们!

圣子耶稣,我们都受他掌握,

你不要让地狱成为我们安身之所,

我们不需要它.也不用对它报恩。

人们啊,决不要对此加以奚落;

请祈求天主,让大家宽恕我们!

(郑克鲁译)

Ballad of the hung men

Human brothers who live while we are no more,

do not harden your hearts against us,

for if you have mercy on us

God will likewise have mercy on you.

You see us tied here by five of six,

as for the flesh we served too much

it is now eaten away and rotten

and we are but bones turning to ash and dust.

Let no one make fun of our misfortune:

rather pray God that He absolves us all!

So, brothers, we pledge you not to

despise us, even though we were brought down

by law. You know well that

all men are not of sound judgement;

forgive us, for we are in fear

that the grace of virgin Mary's son

who could spare us the infernal wrath

could be hexhausted for us.

We are dead, no one dare to harry us;

rather pray God that He absolves us all!

The rain has drenched and washed us,

the sun has parched and blackened us:

magpies and crows have pecked at our eyes

and ripped our beard and eyebrows off.

Never are we seated;

here and there, as the wind changes

at will it swings us ceaselessly,

more pockmarked than thimbles.

So please don't join our brotherhood;

rather pray God that He absolves us all!

Prince Jesus who rules on us all,

protect us from the lordship of hell:

we have no business nor debts here.

Men, this is no laughing matwww.58yuanyou.comter;

rather pray God that He absolves us all!

https://lyricstranslate.com

Ballade de la belle heaumire aux filles de joie

Or y pensez, belle Gantire

Qui m'colire souliez tre,

Et vous, Blanche la Savetire,

Or il est temps de vous connatre,

Prenez dtre ou sentre ;

N'pargnez homme, je vous prie :

Car vieilles n'ont ne cours ne tre ,

Ne que monnoie qu'on dcrie.

Et vous, la gente Saucissire

Qui de danser tes adtre ,

Guillemette la Tapissire,

Ne mprenez vers votrematre :

Tt vous faudra clore fentre ;

Quand deviendrez vieille, fltrie,

Plus ne servirez qu'un vieil prtre,

Ne que monnoie qu'on dcrie.

Jeanneton la Chaperonnire,

Gardez qu'ami ne vous emptre;

Et Catherine la Boursire,

N'envoyez plus les hommes patre;

Car qui belle n'est, ne perptre

Leur male grce, mais leur rie!

Laide vieillesse amour n'emptre

Ne que monnoie qu'on dcrie.

Filles, veuillez vous entremettre

d'couter pour quoi pleure et crie:

Pour ce que je ne me puis mettre,

Ne que monnoie qu'on dcrie.

Ballad of the comely helmet-maker to the ladies of the night

Ponder this, ye pretty glover,

who sought to learn my trade,

And you also, Blanche the cobbler,

now is the time to get acquainted,

pray, pick them all around,

and don't you spare a single man,

for old bags have no more value

than depreciated currency.

As for you, gentle sausage-maker,

who are so apt at dancing,

Guillemette the upholsterer,

don't do your master any wrong:

soon will you have to draw the curtain

as you become old and withered,

of no more use than an old priest

or depreciated currency.

Jeanneton the hood-maker,

don't let a suitor hinder you,

and you, Catherine the purse-maker,

send the men packing no more,

for she who has no beauty gets

no male consent, but jeers instead.

Ugly old age gets no more love

than depreciated currency.

Gals, I pray, take the trouble

to hear the cause of my laments,

for I can no more sell myself

than depreciated currency.

Le Quatrain que feist Villon quand il fut jug mourir

Je suis Francoys, dont il me poise,

Ne de Paris empres Pontoise,

Et de la corde d’une toise

Scaura mon col que mon cul poise.

The quatrain Villon wrote when he was sentenced to death

I am Franois, on me it weighs,

born in Paris, close to Pontoise

and a three feet long rope stands poised

to teach my neck how my ass weighs!

Monseigneur n'est ne mon evesque...

Mon seigneur n'est ne mon evesque,

Soubz luy ne tiens, (1) s'il n'est en friche ;

Foy ne luy doy n'ommaige (2) avecque,

Je ne suis son serf ne sa biche.

Peu m'a d'une (3) petite miche

Et de froide eaue tout ung est ;

Large ou estroit, moult me fut chiche :

Tel luy soit Dieu qu'il m'a est !

Mylord is no bishop of mine

My lord is not bishop of mine

I hold no land of his, but barren

I owe him neither faith nor oath.

A meagre loaf and cold water

were all my lot the wole summer.

A stingy cad to me he was,

so may be God to him as well.

奥斯卡汤普森在他的《德彪西:一个人和一位艺术家》中写道:“即使德彪西像雨果沃尔夫那样仅是一位歌曲作家——如果没有《佩利亚斯与梅丽桑德》,没有《牧神午后》,没有《德塞巴斯蒂安的殉难》,没有《夜曲》、《大海》、《伊比利亚》,没有弦乐四重奏和钢琴作品——德彪西仍然是艺术史上超群绝伦、独树一帜的人物。”德彪西谱的一半以上的诗都是伟大诗人的作品,包括魏尔兰、波德莱尔、马拉美、维克多雨果、缪塞等人的名字都出现在他所用的抒情诗目录里。

从1904年开始,德彪西回到了古代诗人那里,似乎是喜欢上了他们格律的严谨和古典式的平衡。在接受一份报纸的访问时,他承认自己正想根据15世纪的诗人弗朗索瓦维庸的诗谱写一些歌曲。他的《弗朗索瓦维庸的三首叙事歌》(Trois ballades de Franois Villon)完成于1910年。这是作曲家唯一以维庸作品为歌词文本的创作。这组作品最初是为人声和钢琴伴奏而作的,后来又配器成管弦乐队伴奏版。

弗朗索瓦维庸(Franois Villon, 1431-1463)是法国中世纪最杰出的抒情诗人。即使以今天的眼光来看,维庸的生平经历也称得上惊世骇俗。保尔瓦莱里这样描述维庸的形象:“理解维庸作品的困难不能仅仅归因于时代久远,人事已非,还在于作者是个特殊人物。这个才华横溢的巴黎人是个可怕的家伙,他丝毫不同于那时的大学生或资产者……维庸是个特殊人物——因为他的情况在我们这个行当里是绝无仅有的(尽管这个行当在思想上具有冒险精神):一个诗人是强盗,罪大恶极之徒,很可能干过拉皮条的营生,参加过恐怖团伙,靠抢劫过活,会撬锁,见机行凶,始终处于戒备状态。他在感到绞索就套在脖子上的同时还写下了精彩的诗篇。”尽管维庸的身份几乎无法被恰当定义,但作为一名诗人的贡献是再怎样高估都不过分的,用瓦莱里的话说:“诗人或艺术家的贡献……对一些人来说微不足道,对另一些人则意义重大。不存在任何与之相符的东西。这些人只能在一种不太好的社会制度中生存下去,以便最美好的东西得以被创造出来,这些最美好的东西是人创造的,它们反过来也造就了真正的人。”

维庸的诗集抒情、讽刺、哀伤和机趣为一体,感情真挚而又不受拘束。他既描写身边的日常生活,又抒写爱情、青春和梦想,而死亡的阴影则时刻笼罩着他的诗。他有时也玩弄文字游戏,用粗俗的语言表现真情实感,致力于冲破当时社会的种种枷锁。《弗朗索瓦维庸的三首叙事歌》中的第一首《维庸给他情人的叙事歌》(Ballade de Villon s'amye)典型地反映了他的诗歌的这些特征。这是一曲失意爱人的哀歌,整首诗传达出一种复杂的情绪,悲伤、痛苦是和讽刺、幽默夹杂在一起的,而时间永不停息的脚步、衰老和死亡的无可逃避也是诗中的主题之一。

德彪西完全抓住了维庸诗作中那种苦涩、复杂的情绪。人声部分那种朗诵式的音乐被伴奏音乐更多地旋律写作所弥补。德彪西的风格通常被认为是精致而微妙的,特别是在他的歌曲中。然而这首作品除了这一特征以外,还不乏一些强有力的段落(这在德彪西的声乐作品中并不多见),使得整首作品和维庸的诗一样,显示出某种乖张而强烈的特征。

Ballade de Villon s'amye

Faulse beaut, qui tant me couste cher,

Rude en effect, hypocrite doulceur,

Amour dure, plus que fer, mascher;

Nommer que puis de ma deffa?on seur.

Charme felon, la mort d'ung povre cueur,

Orgueil muss, qui gens met au mourir,

Yeulx sans piti! ne veult droict de rigueur

Sans empirer, ung povre secourir?

Mieulx m'eust valu avoir est crier

Ailleurs secours, c'eust est mon bonheur:

Rien ne m'eust sceu de ce fait arracher;

Trotter m'en fault en fuyte deshonneur.

Haro, haro, le grand et le mineur!

Et qu'est cecy? mourray sans coup ferir,

Ou piti peult, selon ceste teneur,

Sans empirer, ung povre secourir.

Ung temps viendra, qui fera desseicher,

Jaulnir, flestrir, vostre espanie fleur:

J'en risse lors, se tant peusse marcher,

Mais las! nenny: ce seroit donc foleur,

Vieil je seray; vous, laide et sans couleur.

Or, beuvez, fort, tant que ru peult courir.

Ne donnez pas tous ceste douleur

Sans empirer, ung povre secourir.

Prince amoureux, des amans le greigneur,

Vostre mal gr ne vouldroye encourir;

Mais tout franc cueur doit, par Nostre Seigneur,

Sans empirer, ung povre secourir.歌词大意:

维庸给他情人的叙事歌

虚伪的美人,你让我付出了那么多,

事实上你是这样粗暴,温柔都是装出来的,

爱情比钢铁还要难以咀嚼;

我可以把你命名为我的毁灭的姊妹,

不忠的美色,贫苦心灵的杀手,

伪装的骄傲能将男人推入死亡,

毫无同情的双眼!严格的公正难道不会

来帮助一个穷人,不让事情变得更糟?

我或许会好过一些,如果我哭着

祈求其他人的帮助,我或许会快乐一些:

但是没有什么可以把我从我追随的道路上拉开;

我必须快步地从耻辱中逃开。

救我,救我,大人和孩子!

这是什么?我会轻而易举地死去吗?

或者怜悯可以,按照这些条款

来帮助一个穷人,不让事情变得更糟?

时间会到来,你的花期

那鲜黄的外表会毫无生气:

然后我会大笑,如果可以的话,

但是,啊!不:那是一件疯狂的事,

我会老,而你也会变得丑陋而苍白。

所以痛饮吧,时光依然奔流不止。

不要把这痛苦交付给每一个人;

来帮助一个穷人,不让事情变得更糟。

爱之君主,爱人们的国王,

我不愿招致你的不快;

但是上帝啊,每一个不受拘束的心灵

来帮助一个穷人,不让事情变得更糟。

第二首《维庸为他的母亲向圣母玛利亚的祷告而作的叙事歌》(Ballade que feit Villon requeste de sa mre pour prier Nostre-Dame)。俄国诗人奥西普曼德尔施塔姆在他的《弗朗索瓦维庸》一文中曾经说到,“中世纪的血液流淌在维庸的血管里。他的诚实,他的性情,他的精神价值的来源,都是拜中世纪所赐。哥特式生理学(别小看中世纪,它恰恰是生理学上辉煌的时代)取代了维庸的世界观,并由于他缺乏与过去的传统纽带而慷慨地奖赏他。”德彪西成功地暗示了这首叙事歌的宗教性,他为之谱写的音乐运用了古老的教会调式,此外,他还通篇使用了精巧的对位技术。音乐整体的编织精致优美,创造出一种中古时期的氛围。

Ballade que Villon feit la requeste de sa mre pour prier Nostre-Dame

Dame du ciel, regente terrienne,

Emperire des infernaulx palux,

Recevez-moy, vostre humble chrestienne,

Que comprinse soye entre vos esleuz,

Ce non obstant qu'oncques riens ne valuz.

Les biens de vous, ma dame et ma maistresse,

Sont trop plus grans que ne suys pecheresse,

Sans lesquelz bien ame ne peult

Merir n'avoir les cieulx,

Je n'en suis mentresse.

En ceste foy je vueil vivre et mourir.

vostre Filz dictes que je suys sienne;

De luy soyent mes pechez aboluz:

Pardonnez-moy comme l'Egyptienne,

Ou comme il feut au clerc Theophilus,

Lequel par vous fut quitte et absoluz,

Combien qu'il eust au diable faict promesse.

Preservez-moy que je n'accomplisse ce!

Vierge portant sans rompure encourir

Le sacrement qu'on celebre la messe.

En ceste foy je vueil vivre et mourir.

Femme je suis povrette et ancienne,

Qui riens ne scay, oncques lettre ne leuz;

Au moustier voy dont suis paroissienne,

Paradis painct o sont harpes et luz,

Et ung enfer o damnez sont boulluz:

L'ung me faict paour, l'aultre joye et liesse.

La joye avoir faismoy, haulte Deesse,

A qui pecheurs doibvent tous recourir,

Comblez de foy, sans faincte ne paresse.

En ceste foy je vueil vivre et mourir.

歌词大意:

维庸为他的母亲向圣母玛利亚的祷告而作的叙事歌

天堂的夫人,尘世的女王,

地狱深处的女王,

请接纳我,你的基督的卑微女仆,

这样我可以被看作你的选民,

即使我不值一文。

我的夫人和女主人,你的永福

远胜过我的罪孽,

没有它,没有一个灵魂可以被应许

进入天堂,我不过是说出了一个真理。

我愿在这个信仰中活着和死去。

你的圣子说我是他的;

通过他我的罪可以被消除:

请宽恕我就像宽恕埃及的妇女,

或者如他的教士提阿非罗所做的,

他被你赦免、宣告无罪,

即使他已经与魔鬼订立了契约。

请用同样的做法来保护我!

处女怀胎,她没有染上罪孽

圣礼在弥撒中举行。

我愿在这个信仰中活着和死去。

我是一个穷苦的老妇人

一无所知;我无法阅读;

在修道院里,我是那儿的一名教区居民,

有一幅天堂的画,画中有竖琴和琉特琴;

还有一幅地狱图景,在那里受罚的人正受着煎熬:

它令我充满恐惧,另一幅画则使我充满喜乐和幸福。

让我得到喜乐吧,伟大的女神,

所有的罪人都必须转向你,

完全被信仰所左右,远离虚伪和懒惰。

我愿在这个信仰中活着和死去。

《弗朗索瓦维庸的三首叙事歌》的最后一首《巴黎女人的叙事歌》(Ballade des femmes de Paris)则完全展现出维庸诗歌的那种风趣幽默乃至恶作剧的倾向。德彪西为人声所写的音乐充分塑造出了原诗中的巴黎女人那种聒噪和喋喋不休。在钢琴伴奏的版本中,钢琴也参与到对话中来,最后部分钢琴的滑奏更是增添了那种风趣幽默的效果。在管弦乐队版中,作曲家通过弦乐的拨奏以及疾驰的木管和铜管乐器演奏的插段达到了一种更为立体和丰富的效果。如果说之前那首祈祷歌让我们联想到中世纪晚期和文艺复兴早期的宗教题材的尚松的话,这首《巴黎女人的诗》则让人联想到世俗尚松,比如克莱芒雅内坎的作品。

Ballade des femmes de Paris

Quoy qu'on tient belles langagires

Florentines, Veniciennes, assez pour estre messaigires,

Et mesmement les anciennes;

Mais, soient Lombardes, Romaines, Genevoises,

mes perils, Piemontoises, Savoysiennes,

Il n'est bon bec que de Paris.

De beau parler tiennent chayeres,

Ce dit-on Napolitaines,

Et que sont bonnes cacquetires

Allemandes et Bruciennes;

Soient Grecques, Egyptiennes,

De Hongrie ou d'aultre pas,

Espaignolles ou Castellannes,

Il n'est bon bec que de Paris.

Brettes, Suysses, n'y savent gurres,

Ne Gasconnes et Tholouzaines;

Du Petit Pont deux harangres les concluront,

Et les Lorraines, Anglesches ou Callaisiennes,

(ay-je beaucoup de lieux compris?)

Picardes, de Valenciennes...

Il n'est bon bec que de Paris.

Prince, aux dames parisiennes,

De bien parler donnez le pr原由网ix;

Quoy qu'on die d'Italiennes,

Il n'est bon bec que de Paris.

歌词大意:

巴黎女人的叙事歌

虽然佛罗伦萨和威尼斯的女人

可能拥有健谈的名声,

能够将他们的信息传达,

甚至年老的都能如此;

虽然伦巴第或者罗马的女人也有同样的名声,

甚至日内瓦的也可能是这样,

或者皮得蒙或萨瓦的也是如此,

但是没有人能像巴黎的女人那样鼓噪。

人们说那不勒斯的女人

拥有健谈的地位,

日耳曼和普鲁士的女人

最擅于喋喋不休;

但无论是希腊的,埃及的,

匈牙利的或者无论哪里的

西班牙的还是卡斯蒂利亚的,

没有人能像巴黎的女人那样鼓噪。

布列塔尼和瑞士女人无可匹敌,

还有加斯科尼和图卢兹的女人;

小桥上两个卖鱼的女人

会在她们面前停下来,还有洛林人

或者英格兰或加莱人

(地名够了吗?)

或者皮卡底或者巴伦西亚人……

但是没有人能像巴黎的女人那样鼓噪。

王子,把最长舌奖

颁给巴黎女人;

让人们继续谈论意大利人,

但是没有人能像巴黎的女人那样鼓噪。

|

《古美人谣》| 弗朗索瓦维庸

您可知,在哪个国家,

可寻罗马女神芙罗拉;

希腊哲人阿希比雅达,

和其姊妹黛伊丝;

回音宛转,人声飘荡

越过河流与池塘,

此等惊为天人之佳丽何处觅?

然旧岁之雪又在何方!

何处可寻才女爱洛依丝?

圣丹尼的阿伯拉尔,

苦于为她深深所迷,

而被净身当了修士。

还有,那位皇后害得

布里丹在袋中被沉入塞纳河

又何处可寻其鬓影衣香?

然旧岁之雪又在何方!

艳如百合的白色皇后,

有着人鱼般的歌喉,

大脚伯莎,碧昂特丽丝,爱丽丝,

曼恩领主阿行布吉,

还有在鲁昂被英国人烧为灰烬的

洛林圣女贞德;

圣母啊,她们何处可寻访?…

然旧岁之雪又在何方!

献词

王子啊,今年今月莫再打探

昔日美人于何处盘桓,

这首歌谣只不过在吟唱:

然旧岁之雪又在何方!

(庾如寄译,2019年秋)

法语原诗(现代法语版)

Ballade des dames du temps jadis

(En franais moderne)

Dites-moi o, n'en quel pays,

Est Flora, la belle Romaine ;

Archipiada, et Thas,

Qui fut sa cousine germaine ;

cho, parlant quand bruit on mne

Dessus rivire ou sur tang,

Qui beaut eut trop plus qu'humaine ?

Mais o sont les neiges d’antan !

O est la trs sage Hlos,

Pour qui fut chtr et puis moine

Pierre Esbaillart Saint-Denis ?

Pour son amour eut cette peine.

Semblablement, o est la reine

Qui commanda que Buridan

Ft jet en un sac en Seine ?

Mais o sont les neiges d'antan !

La reine Blanche comme un lis,

Qui chantait voix sirne,

Berthe au grand pied, Bietris, Allys,

Harembourgis, qui tint le Maine,

Et Jeanne, la bonne Lorraine,

Qu'Anglais brlrent Rouen ;

O sont-ils, Vierge souveraine ? ....

Mais o sont les neiges d'antan !

Envoi

Prince, n'enqurez de semaine

O elles sont, ni de cet an,

Que ce refrain ne vous remaine :

Mais o sont les neiges d'antan !

诗中的女性角色注释(附油画)

*Flora,芙罗拉,罗马神话里的花神。为花之精灵Chloris逃避西风之神Zephyrus追逐时所化。其形象经常出现在西方油画中,如波提切利(Sandro Botticelli)《春》,提香(Tiziano Vecelli)《花神》。

波提切利《春》,花神为右三

提香《花神》

* Archipiada,阿希比雅达,应该为Hipparchia (fl. 300 B.C.E.),古希腊犬儒主义女哲学家,其丈夫Crates of Thebes亦属该派。简介见注脚[3]。有说法认为Archipiada为柏拉图《会饮篇》中Alcibiades[4]之误,实非。

*Thas(fl. 300 B.C.E.),黛伊丝,古希腊名妓。曾随亚历山大大帝远征,著名事迹为煽动亚历山大焚烧伊朗古城波斯波利斯。简介见注脚[5]。约书亚雷诺兹(Joshua Reynoldsre)的油画《Thais of Ahens with Tourch》即是描绘这段历史。

约书亚《thais of Athen with torch》

* Hlos(c. 1090?/1100?-c.1164),爱洛伊斯(梁实秋译作“哀绿绮思“),法国思想家,主要成就在道德哲学领域,著有《书信集》、《问题集》。简介见注脚[6]。

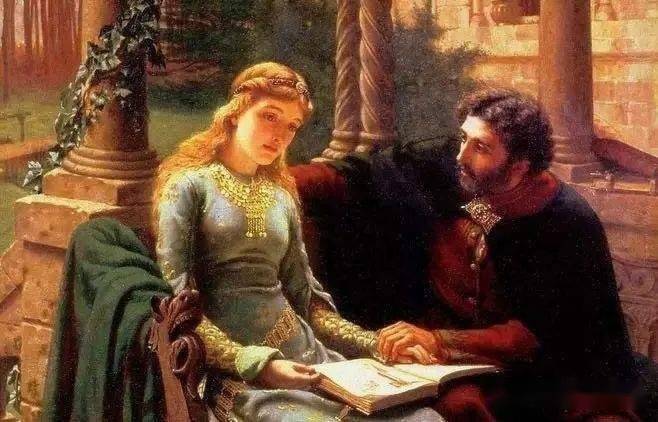

爱洛伊斯与阿伯拉尔

*Pierre Esbaillart即Pierre Abelar(c.1079-c.1142),阿伯拉尔,法国神学家、哲学家。阿伯拉尔曾为爱洛伊斯的教师,后二人相恋,后者在否认婚姻后被送入女修道院,而前者则被爱洛伊斯叔父阉割,之后成为修士。(P.S.二人故事可参看电影《天堂窃情》)

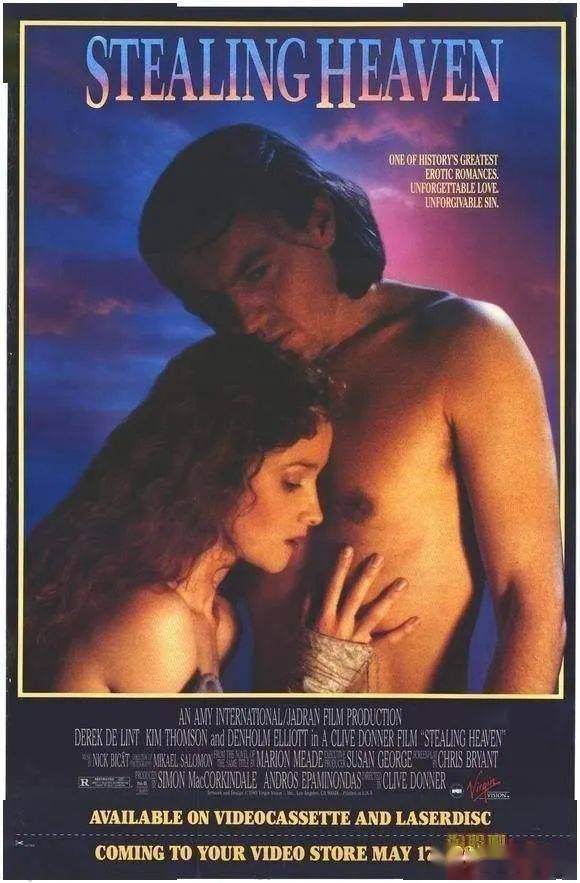

《天堂窃情》电影海报

* La reine即路易五世的王后Marguerite de Bourgogne(c.1290-c.1315),因出轨而被国王囚禁在城堡中[7],不久病亡。

*Buridan(c.1301–c.1359/62), 布里丹,法国哲学家,著名理论有“布里丹的驴”。传说因与王后通奸而被路易五世装进袋子仍入塞纳河[8],但并无史料证明其真实性。

*La reine Blanche,即Blanche de Castille(c.1188-c.1252),路易八世的王后,布兰卡太后。年幼的路易九世登基后,成为摄政太后,归政之后仍在幕后操纵国政直至逝世。她与其子创造了中世纪法国的黄金时代。

Joseph Marie Vien《路易九世将摄政大权托付给布兰卡太后》

* Berthe au grand pied即Bertrade de Laon(c.720-c.783),大脚伯莎,丕平三世(即矮子丕平Ppin le Bref,c.714-c.768)的王后。

*Bietris, 即Beatrice Portinari (c.1265 –c.1290),碧昂特丽丝,一个意大利女子,疑为诗人但丁作品《新生》的主要灵感来源,以及《神曲》中他暗恋的情人和灵魂导师。简介见注脚[9]。

Henry Hol原由网iday《Dante meets Beatrice》

*Allys,爱丽丝,即Adlade of Paris (or Alis) (c. 850/853 – c.901) , 西法兰克王后,路易二世的第二任妻子,在政治斗争中辅佐其子查理三世上位。

* Harembourgis, 阿行布吉,即Ermengarde(?-c.1126),Countess of Maine[10] and Lady of Chteau-du-Loir,曼恩女伯爵(是女伯爵,不是伯爵夫人,她是曼恩领主, 爵位是从她爹那继承的)及卢瓦尔城堡女主人,安茹领主富尔克五世(Fulk V of Anjou)的妻子。简介见注脚[11]。

* Jeanne,即Jeanne d'Arc(c.1412-c.1431),圣女贞德。法国民族英雄,在英法百年战争中带领法国军队对抗英军入侵,最后被英格兰控制的宗教裁判所以异端和女巫罪判处火刑,在鲁昂当众烧死。

赫尔曼《贞德在火刑柱上》

译本一:程曾厚《历代淑女歌》(《法国诗选》,复旦大学出版社)

英萝拉是罗马城的佳丽,

请告诉我,她在何处羁留?

阿基比达如今又在哪里,

还有泰伊丝,前者的女友?

还有厄科,话音掠过河流,

她的声音会在水上回荡,

人间无此绝色,天上才有?

去岁下的雪,今又在何方?

才女爱洛伊丝何处归依?

阿贝拉为爱她被阉以后,

当了修士,终生颠沛流离,

最后去圣德尼,吃尽苦头。

再说,何处又是这位王后,

她一声令下,就把布里当

捆在袋中往塞纳河里丢。

去岁下的雪,今又在何方?

白王后可和百合花相比,

她更有美人鱼般的歌喉,

大脚的贝特,艾丽斯,尤其

阿杭布吉握有曼恩在手,

还有贞德,这洛林的闺秀

被英军活活烧死在卢昂?

她们在哪里?圣母,请开口!

去岁下的雪,今又在何方?

君王啊,请不必问个不休,

究竟何处可求这些女郎,

纵然再问,我的回答依旧:

去岁下的雪,今又在何方?

译本二:杨德友《歌谣:往日的贵妇》

告诉我,在哪里,在哪块土地,

如今还能找到罗马丽人芙罗拉

或者泰伊丝——她异常妩媚,

或者她的表姊阿基皮达?

或者爱果——她是回声,回答。

重复飘过湖面、河面的话语,

她的美丽足以令世人羞杀,

但是,去年的白雪如今安在?

聪明的海萝伊丝在哪里?

因为她,皮尔阿贝拉二受阉割,

又再圣德尼修道院受戒,

因为爱她受尽种种折磨。

如今那位王后又在何处?——

她下令把布里坦装入麻袋,

然后投入塞纳河,是为惩处:

但是,去年的白雪如今安在?

布朗皇后白皙一如百合花,

歌声又堪与美人鱼媲美,

还有贝阿丽丝、阿丽丝、大脚贝塔,

还有迷住海因的阿伦堡姬,

还有贞德——洛林的淑女,

被英国人烧死在鲁昂——

啊,圣母,如今她们都在哪里?

但是,去年的白雪如今安在?

公子啊,今年或者这个星期,

请莫问她们在何处徘徊。

我只想让你记住短话一句:

但是,去年的白雪如今安在?

译本三:Dante Gabriel Rossetti《The Ballad of Dead Ladies》

Tell me now in what hidden way is

Lady Flora the lovely Roman?

Where's Hipparchia, and where is Thais,

Neither of them the fairer woman?

Where is Echo, beheld of no man,

Only heard on river and mere,--

She whose beauty was more than human?...

But where are the snows of yester-year?

Where's Heloise, the learned nun,

For whose sake Abeillard, I ween,

Lost manhood and put priesthood on?

(From Love he won such dule and teen!)

And where, I pray you, is the Queen

Who willed that Buridan should steer

Sewed in a sack's mouth down the Seine?...

But where are the snows of yester-year?

White Queen Blanche, like a queen of lilies,

With a voice like any mermaiden,--

Bertha Broadfoot, Beatrice, Alice,

And Ermengarde the lady of Maine,--

And that good Joan whom Englishmen

At Rouen doomed and burned her there,--

Mother of God, where are they then?...

But where are the snows of yester-year?

Nay, never ask this week, fair lord,

Where they are gone, nor yet this year,

Except with this for an overword,--

But where are the snows of yester-year?

英文直译本| literal translation

Ballade of Ladies of Time Gone By

Tell me where, in which country

Is Flora, the beautiful Roman;

Archipiada, or Thas

Who was her first cousin;

Echo, speaking when one makes noise

Over river or on pond,

Who had a beauty too much more than human?

Oh, where are the snows of yesteryear!

Where is the very wise Hlose,

For whom was castrated, and then (made) a monk,

Pierre Esbaillart (Abelard) in Saint-Denis?

For his love he suffered this sentence.

Similarly, where is the Queen (Marguerite de Bourgogne)

Who ordered that Buridan

Were thrown in a sack into the Seine?

Oh, where are the snows of yesteryear!

The queen Blanche (white) as a lily (Blanche of Castile)

Who sang with a Siren's voice;

Bertha of the Big Foot, Beatrix, Aelis;

Erembourge who ruled over the Maine,

And Joan (Joan of Arc), the good (woman from) Lorraine

Whom the English burned in Rouen;

Where are they, oh sovereign Virgin?

Oh, where are the snows of yesteryear!

Prince, do not ask me in the whole week

Where they are - neither in this whole year,

Lest I bring you back to this refrain:

Oh, where are the snows of yesteryear!

古法语原文

Ballade des dames du temps jadis|En ancien franais

Dictes moy o, n'en quel pays,

Est Flora, la belle Romaine ;

Archipiada, ne Thas,

Qui fut sa cousine germaine;

Echo, parlant quand bruyt on maine

Dessus rivire ou sus estan,

Qui beaut eut trop plus qu'humaine?

Mais o sont les neiges d'antan!

O est la trs sage Helos,

Pour qui fut chastr et puis moyne

Pierre Esbaillart Sainct-Denys?

Pour son amour eut cest essoyne.

Semblablement, o est la royne

Qui commanda que Buridan

Fust jett en ung sac en Seine?

Mais o sont les newww.58yuanyou.comiges d'antan!

La royne Blanche comme ung lys,

Qui chantoit voix de sereine;

Berthe au grand pied, Bietris, Allys;

Harembourges qui tint le Mayne,

Et Jehanne, la bonne Lorraine,

Qu'Anglois bruslerent Rouen;

O sont-ilz, Vierge souveraine ?

Mais o sont les neiges d'antan!

Prince, n'enquerez de sepmaine

O elles sont, ne de cest an,

Qu' ce refrain ne vous remaine:

Mais o sont les neiges d'antan!

遗言(节选)

在我一生的第三十个年头.

我早已蒙受了一切耻辱……

我珍惜我青春的时光,

那时我比旁人更多地纵情玩乐,

直到暮年终于来访,

达晚年却对我隐瞒了动身的时刻。

我的韶华既不曾徒步而行,

也没有骑马而去:唉!怎么办?

我飞逝的韶光突然不见踪影,

竟没给我留下什么纪念。

青春逝去.我独自留下来,

缺乏知识,缺乏理性,

忧郁,慌张,比桑果更悲哀,

没有财产,没有年金。

说实话,我最微贱的亲友

都不认我,都不回头看我一眼,

连天职都抛之脑后,

只因为我没有几个钱……

唉!上帝啊,假如我读过书,

在我疯狂的青年时代,

献身于善良的风俗,

我会有个家,睡得畅快。

但怎么样呢?我竟逃避了学习,

像坏孩子的行为。

一提起这件往事,

我就禁不住心碎……

我的岁月在飘泊中消逝……

我再不害怕谁将我纠缠,

因为一切都归结于死亡。

和蔼的放荡之辈今在何方?

往日我曾经将他们追随,

他们口若悬河,纵情歌唱,

他们的言行是那么富于趣味!

他们全都与世长辞,

谁也不再在这人间逗留,

但愿上帝将幸存者拯救!

……我知道,神甫与俗子,

穷汉与富翁,平民与贵族,

智者与笨伯,吝啬鬼与慷慨之士,

美丈夫与丑八怪,无名小车与大人物,

卷起衣领的少妇,

无论怎样的身份,

头上顶着瓦耀或挂着珍珠,

都毫无例外地躲不过死神。

且任帕里斯或埃菜娜失去影踪,

无论谁满怀着痛苦离开人间,

都无异于透过一口气,吹过一阵风:

他的辛酸从心头破裂消散,

只有上帝才知道他流过怎样的汗水!

没右谁减轻他的痛苦:

纵然是兄弟或姐妹

也不愿代替一个孩子进入坟墓。

死亡使他吓得脸色发白,不断战栗

低下头,拉紧血管,

缩起脖子,肌肉变得软弱无力,‘

关节与神经都扩大伸展。

女性的肉体啊,你是如此柔软。

光滑而细嫩,如此宝贵,

你不需要等待这些痛苦的熬煎?

这可是活生生地向天国远走高飞。

(张秋红译)

回旋诗

……当我将坟场上

所堆积的骷髅细看,

所有这些死者至少是诉状

审理庭的法官,

或者是提篮叫卖的小贩:

我可以让它们互相代替;

因为从主教与路灯看守之间,

我看不出有什么差异。

这些死者生前有的人

卑微,有的人骄倨,

有的人贵为天子至尊,

有的人沦为奴仆,充满恐惧,

我从这里看到大家共同的结局,

只见他们乱糟糟地挤成一团。

他们的领地已被人夺去;

教士或主子都无从分辨。

如今他们离开了人间.上帝守着亡魂!

至于肉体,他们已经腐烂。

无论他们曾是贵妇或贵人,

养尊处优,恣意寻欢,

吃尽乳油、麦糊或米饭,

他们的尸骨都化为尘土,

他们的欢声笑语都烟消云散。

但愿乍慈的耶稣将他们宽恕!……

(张秋红译)

歌行:布卢瓦诗会之歌

我渴得要死,虽然身旁有池沼,

我热得发烫,又冷得牙齿打架;

我住在自己国内遥远的一角;

我靠着炭火,浑身打颤火辣辣;

我穿得像帝王,脱下一丝不挂,

我含泪而笑,绝望地等个没完;

我失望已极,才会越来越勇敢;

我欢欣喜悦,却感到兴趣全无;

我体魄强健,却既无力,又无权,

我处处受欢迎,又被人人厌恶。

靠不住的东西对我才最可靠;

明明白白的事物才让人摸瞎;

我看肯定的东西才问题不少;

意外的事件才使我见识增加,

我全都到手,却永远是个输家;

天一亮,我就说:“上帝赐你晚安!”

我生怕跌下来,明明仰卧朝天;

我身上不名一文,仍有吃有住;

我无人可以继承,却盼望遗产,

我处处受欢迎,又被人人厌恶。

我无所用心,又全力以赴寻找。

我想获取不想要的财富身价;

谁对我和蔼可亲,其实更奸刁,

他使我迷路,却对我句句真话;

此人要我相信,本来黑的乌鸦

就是白的天鹅,这样才算伙伴;

我以为害我者还是与人为善;

谎言和真理对我是同一事物;

我都记住,但头脑里一片黑暗,

我处处受欢迎,又被人人厌恶。

宽厚的君王○1,我恳请你能明断,

我什么都懂,可又是真伪莫辨:

我与众不同,又毫不比人特殊。

我还知道什么? 收回抵押的钱○2,

我处处受欢迎,又被人人厌恶。

注○1实指奥尔良的查理。

○2可见维庸作诗•对查理不无经济要求。

(题解)奥尔良的查理在其布卢瓦的小朝廷内,不时组织诗会,规定首句,自己以身作则,并邀各诗人按韵填诗。据考,诗会并非一次性的颁奖竞赛。“我渴得要死,虽然身旁有池沼”由查理出题,他自己在1451年成诗。维庸于1457年左右潜逃在外,途经布卢瓦,当然希望受到接待,得到保护,作成此诗,收录在查理御笔抄录的手稿内。这首诗看似文字游戏,但评家多认为其中藏有真言,有维永辛酸的人生体会,而“我含泪而笑”,更是维永个人的绝妙写照。

(程曾厚译)

维庸身心之争歌

(又名《维庸和良心的对话》)

是什么声音? ——是我!——是谁? ——你的心。

你的心己到岌岌可危的地步:

看到你像丧家之犬,叫人怜悯,

腾缩在角落里,又寂寞,又孤独,

我就浑身无力,我就劲头不足。——

这是为什么? ——因为你游手好闲。——

与你何干? ——是我倒霉,是我受难。——

你别烦我! ——干吗? ——我以后再思考。

等到什么时候? ——等我度完童年。

我就不再啰嗦。——这样对我才好。——

你想什么时候? ——等我立身做人。

你三十了:骡子已可老马识途;

还是孩子? ——不是。——你是头脑发昏,

鬼迷心窍? ——怎么迷法? 把心迷住?

你一窍不通。——不,苍蝇掉进牛乳;

黑是黑,自是白,区别一目了然。——

就这些? ——你干吗要我说个没完?

你要是不够,我还有例子奉告。

你完蛋了! ——我不会认输就完蛋。——

我就不再啰嗦。——这样对我才好。

我真担忧,你有错误,又有酸辛。

如果你是可怜的傻瓜,是废物,

那你又怎么会表示事出有因,

可你美丑不分,凡事可有可无。

也许,你的脑袋更比石头顽固,

也许,堕落更比荣耀讨你喜欢!

你如何回答这样的分析推断?

眼睛一闭,我就可以一了百了。

天哪,还自欺欺人! ——你能言善辩!

我就不再啰嗦。——这样对我才好。

为何如此坎坷? ——是我太不走运。

是土星安排好我命中的祸福,

我想,是土星的祸根。——奇谈怪论!

你是命的主人,却自认是奴仆。

看看所罗门写下的智慧大书:

“智者可以让天上的星宿就范,

可以使星星的作用或明或暗。”

我不信;我的形象由星宿塑造。

你尽胡说!——真的,这是我的信念。

我就不再啰嗦。——这样对我才好。

你想活吗?愿老天保我平安!

那你应该……——应该什么? ——悔恨羞惭,

不断学习。——学什么? ——学问和磨练,

不再和小人交往!——我一定做到。

要记住这些道理! ——我牢记心间。

别等事情不可收拾,悔之已晚,

我就不再啰嗦。——这样对我才好;

(题解)作家把自己内心世界里的两种思想,或矛盾,或对立,借两个人物,两个隐喻,以争辩对话的形式写成诗,这在中世纪是习见的手法,并非维庸独创。这种手法始于戴尚,奥尔良的查理也多次用过,据研究,本诗作于1461年,维永当时被关押在墨恩地方的狱中,这是一个人面对自我的沉思。对话没有绝对的结论,只是理智占了上风而已、诗题并非维永所加,近代评论家认为习用的诗题欠妥,建议改作《维庸和良心的对话》。

(程曾厚译)

美丽的制盔女

我恍惚觉得我听见

旧日的美人——制盔女

徒然在把青春呼唤,

哀叹着年华的逝去:

“衰老啊!你残酷而阴郁,

为什么这么早击倒了我?

是什么不让我立即死去,

一刀就结束这种折磨?

你剥夺了我至上的魅力,

它使得教士、执事和商贩

无不倾倒于我的美丽,

当时凡是父母生的儿男

谁都愿为我倾家荡产,

毫不顾及后悔和烦恼。

他们求之于我的,到今天

白送给乞丐也遭嗤笑!

我把许多男子一一拒绝,

(你们瞧我有多么傻!)

却爱上了一个奸诈的冤孽,

把无限柔情全献给了他。

尽管我对别人把手腕耍,

我对他可是一片真心!

他对我呢,却粗暴践踏,

他爱的仅仅是我的金银。

尽管他蹂躏我虐待我,

我对他的爱情依然如故;

哪怕他把我在地上拖,

只要叫我吻他,只要他吩咐,

我就忘掉了一身痛楚,

只求这恶贼的一点体贴……

他给了我什么好处?

到如今只剩下耻辱和罪孽。

他死去已经三十年岁月,

而我活着,变了白发婆婆。

每当我追忆往昔的欢悦,

对比当年的我和今日的我,

每当我看见自己全身赤裸,

看见我的身体已经变形,

可怜,枯萎,瘦小,皱缩,

我觉得我马上就要发疯。

哪儿去了,那额头洁白晶莹,

那金发灿烂,那双眉弯弯?

哪儿去了,那宽敞的眼睛,

那无人能抵御的顾盼?

还有笔直的鼻子匀称好看,

优美的耳朵小巧玲珑,

下巴的酒窝,面颊的曲线,

还有那嘴唇甜美、艳红?

哪儿去了,双肩雅致纤细,

美丽的手,修长的臂膀,

还有娇小的双乳耸起,

挺拔的腰股丰满、修长,

正适合做爱的竞技场;

而在宽广的腰股之间

有神秘而迷人的力量

隐藏在这座微小的花园?

啊,额头起了皱,金发已灰白,

眉毛已脱尽,眼睛已昏昧,

失去了顾盼传情的神采,

这曾经使多少人心醉!

鼻子勾了,失去了优美,

耳朵下垂,盖着苔藓层层,

下巴起皱,面颊色如死灰,

而嘴唇犹如皮革制成。

人的美,就这样告终!

背已驼了,双肩已佝偻,

玉臂僵缩,手挛缩成爪形,

双乳呢?干瘪到一无所有

腰股也与乳房一样干瘦,

迷人的宝藏啊,全然凋残!

玉腿萎缩得那么丑陋,

像腊肠似的污迹斑斑……

我们就这样哀叹着往昔,

几个老妇人,呆傻、憔悴,

瑟缩着蹲在秋风里,

依偎着幽暗的火堆,——

一把麻秆刚燃起光辉,

顷刻之间已经烧完。

啊,我们曾是那么娇美!

但这条路啊,谁人能免?”……

(飞白译)

Franois Villon

1431–1463

The Ballad of Villon and Fat Madge

BY FRANOIS VILLON

TRANSLATED BY ALGERNON CHARLES SWINBURNE

‘’Tis no sin for a man to labour in his vocation.’ -Falstaff

‘The night cometh, when no man can work.’

What though the beauty I love and serve be cheap,

Ought you to take me for a beast or fool?

All things a man could wish are in her keep;

For her I turn swashbuckler in love’s school.

When folk drop in, I take my pot and stool

And fall to drinking with no more ado.

I fetch them bread, fruit, cheese, and water, too;

I say all’s right so long as I’m well paid;

‘Look in again when your flesh troubles you,

Inside this brothel where we drive our trade.’

But soon the devil’s among us flesh and fell,

When penniless to bed comes Madge my whore;

I loathe the very sight of her like hell.

I snatch gown, girdle, surcoat, all she wore,

And tell her, these shall stand against her score.

She grips her hips with both hands, cursing God,

Swearing by Jesus’ body, bones, and blood,

That they shall not. Then I, no whit dismayed,

Cross her cracked nose with some stray shiver of wood

Inside this brothel where we drive our trade.

When all’s made up she drops me a windy word,

Bloat like a beetle puffed and poisonous:

Grins, thumps my pate, and calls me dickey-bird,

And cuffs me with a fist that’s ponderous.

We sleep like logs, being drunken both of us;

Then when we wake her womb begins to stir;

To save her seed she gets me under her

Wheezing and whining, flat as planks are laid:

And thus she spoils me for a whoremonger

Inside this brothel where we drive our trade.

Blow, hail or freeze, I’ve bread here baked rent free!

Whoring’s my trade, and my whore pleases me;

Bad cat, bad rat; we’re just the same if weighed.

We that love filth, filth follows us, you see;

Honour flies from us, as from her we flee

Inside this brothel where we drive our trade.

I bequeath likewise to fat Madge

This little song to learn and study;

By god’s head she’s a sweet fat fadge,

Devout and soft of flesh and ruddy;

I love her with my soul and body,

So doth she me, sweet dainty thing.

If you fall in with such a lady,

Read it, and give it her to sing.

Although his verse gained him little or no financial success during his life, Francois Villon is today perhaps the best-known French poet of the Middle Ages. His works surfaced in several manus shortly after his disappearance in 1463, and the first printed collection of his poetry—the Levet edition—came out as early as 1489. More than one hundred printed editions followed, and Villon’s poetry has been translated into more than 40 languages. At the request of King Francis I, the poet Clement Marot prepared the first critical edition of Villon’s work in 1533. Basing his edition on previous printed editions, Marot supplemented it “avecques l’ayde de bons vieillards qui en savent par cueur” (with the aid of good old men who know it by heart). That old men had learned Villon’s work by heart and that Marot’s edition went through fifteen reprintings from 1533 to 1542 attest to the poet’s popularity. Francois Rabelais mentions Villon in Les horribles et epouvantables faits et prouesses du tres renomme Pantagruel, roy des Dipsodes (The Horrible and Terrifying Deeds and Words of the Renowned Pantagruel, King of the Dipsodes, 1532) and quotes from his poetry in the Quart livre (Fourth Book, 1548). Over the next five hundred years such widely different authors as the classical French critic Nicolas Boileau, the English poet A. C. Swinburne, and the American poet Ezra Pound praised Villon. Villon’s life has been romanticized in novels, plays, and motion pictures, and many modern literary anthologies cite him as the best of the late medieval poets in France.

Much of Villon’s popularity arises from sympathy for the difficult life he led, which is described with both humor and poignancy and at great length in his largely autobiographical poetry. In fact, little is known for certain of Villon’s life beyond what he relates. In two court documents dated January 1456 he is referred to as “Francois des Loges, autrement dit de Villon” (Francois des Loges, otherwise called de Villon) and “Francois de Montcorbier.” Most scholars agree that Montcorbier and Villon were one and the same.

From a remark in the first line of Le Testament, which he wrote in 1461 at the age of thirty, one can surmise that Villon was born of poor parents in 1431:

Povre je suis de ma jeunesse

De povre et de petite extrasse;

Mon pere n’eust oncq grant richesse,

Ne son ayeul, nomme Orace;

Povrete tous nous suit et trece.

Sur les tumbeaux de mes ancestres,

Les ames desquelz dieu embrasse!

On n’y voit couronnes ne ceptres.

(Poor I am, and from my youth,

Born of a poor and humble stock.

My father never had much wealth

Nor yet his grandfather, Orace.

Poverty tracks us, every one.

Upon the tombs of my ancestors,

The souls of whom may God embrace!

Sceptres and crowns aren’t to be seen.)

Villon apparently knew little about his father, but in Le Testament he refers to his mother as still living. He spent his early years as a student at the University of Paris in the home of Guillaume de Villon, a respected lawyer, whom he calls in Le Testament his “plus que pere . . . / Qui este m’a plus doulx que mere” (more than father . . . / Who’s been to me kinder than a mother), and he later adopted Guillaume’s surname, at least for his poetry.

By his own admission Villon was not a serious student. During his university years he either took part in or observed an incident in which, as a prank, students stole a stone called “le Pet au diable” (the Devil’s Fart) from the property of a Mademoiselle de Bruyeres and were dealt with harshly. In Le Testament Villon says that he wishes to bequeath a work that he wrote, titled Le romaunt du Pet au deable (The Romance of the Devil’s Fart), to Guillaume; but the work, if it ever existed, has been lost. Villon

participated in many other pranks and brawls during his student years that brought him into conflict with the authorities, but he earned a baccalaureate in 1449 and a master of arts in 1452.

Three years later, a much more serious affair led to Villon’s abrupt departure from Paris. In June 1455 he was attacked by a priest, Philippe Sermoise, who cut his lip with a large dagger; in self-defense, Villon wounded Sermoise in the groin with a small dagger he kept under his cloak. When the priest did not desist from the attack, Villon hit him in the head with a rock. Villon went to a barber to have his wound dressed, giving the false name Michel Mouton. Before Sermoise died, he named Villon as his assailant, and Villon fled. Through the intervention of his friends and, no doubt, his adoptive father, Guillaume, he was granted a full pardon for an act of justifiable homicide, and he returned to Paris in January 1456.

Shortly before Christmas, however, Villon was in trouble with the authorities again: he and three others stole five hundred ecus from the College de Navarre, and one of his accomplices, Guy Tabarie, named Villon as the ringleader. Villon fled Paris a second time. Before his departure he wrote Le Lais (The Legacy, 1456), bequeathing his possessions, both real and imaginary, to his friends.

The next four years of wanderings are ill documented. Villon may have spent some time at the court of Duke Charles d’Orleans at Blois; three of his poems appear in the duke’s personal album. He wrote one of them in praise of the duke’s daughter, Marie d’Orleans, either at her birth on 19 December 1457 or at her entry into Orleans on 17 July 1460. In any case, what protection he may have found at the duke’s court was short- lived. According to Le Testament, he was imprisoned at Meung-sur-Loire in the summer of 1461 for an unnamed, and perhaps minor, offense by order of the bishop of Orleans, Thibaut d’Aussigny. There, again according to Le Testament, he was starved and possibly tortured; but when the new king, Louis XI, traveled through Meung-sur-Loire on 2 October 1461, Villon was liberated along with other prisoners.

Back in Paris, Villon was again imprisoned for a minor offense. While in custody he was recognized as a participant in the College de Navarre robbery. He was released after being sentenced to pay 120 ecus over the next three years for the crime. A few months later he was arrested for a trivial role he played in a street brawl, taken to the Chatelet, subjected to water torture, and condemned to death. He appealed to Parlement, and his sentence was commuted on 5 January 1463 to ten years’ exile from the city. After this third and, apparently, last departure from Paris, Villon disappears from history. Most critics surmise that he died shortly thereafter because he says in Le Testament and in some of his Poemes varies (Miscellaneous Poems, 1450?–1463) that he is a broken man, both physically and financially, who feels that he can no longer count on his friends.

If Villon had died in the prison of Meung-sur-Loire in the summer of 1461, he would probably have vanished poetically as well as personally. Up to that time he had only written Le Lais, which is for the most part an immature work. Written in 1456, according to the first stanza, the poem consists of approximately three hundred verses grouped into octaves. Adopting the mock- testamentary form that he later used with greater skill in Le Testament, Villon says that he is about to leave Paris because he has been unhappy in love—a stock poetic commonplace:

Me vint le vouloir de briser

La tres amoureuse prison

Qui faisoit mon cueur debriser.

(The longing came on me to break

Away from love’s imprisonment,

Which had my heart at breaking point.)

Villon makes no mention of his legal problems, which most critics cite as the real reason for his departure. Before leaving, he bequeaths his nonexistent or valueless property to his friends and relatives. For instance, he wills his “renown,” which could not have been great at that point, to Guillaume de Villon; his heart, enclosed in a shrine, to his faithless lover; and several tavern signs, such as Le Beuf Couronne (The Crowned Ox), to various friends and acquaintances. To the poorhouses he leaves his window frames draped with cobwebs and to his barber, his hair clippings. Villon signs Le Lais in the last stanza.

Although Le Lais is hardly a great work of art, the poem provides a glimpse at the poetic genius that Villon later revealed in Le Testament. Pierre Champion points to Villon’s wanderings and hardships during his exile from Paris and the time he spent in the Meung-sur-Loire prison as the major contributing factors to the more mature style of Le Testament, written only five years later. The complete poem consists of 2,023 verses; the octaves that form the will proper are interspersed with ballades that may have been written at an earlier date and inserted into the work.

Le Testament begins with a tirade against Villon’s jailer at Meung-sur- Loire, Thibaut d’Aussigny: “Mon seigneur n’est ne mon evesque” (My lord he’s not, my bishop not). He goes on to praise Louis XI and thank the king for his release: may Louis live as long as Methuselah, produce twelve male heirs, and one day see paradise as his reward. Because of the harsh conditions of his imprisonment, Villon says, his mental and physical health is poor. In stanza 22 he says that he now regrets his misspent youth:

Je plains le temps de ma jeunesse

(Ouquel j’ay plus qu’autre galle

Jusqu’a l’entree de viellesse)

(I mourn the season of my youth

[When, more than most, I lived it up

Until old age came upon me]).

The mood in this work is much darker than in the earlier Lais; Villon freely vents his hatred not only for d’Aussigny but also for others who have left him poor and friendless.

Le Testament, however, is not simply a long litany of complaints and regrets. In stanza 29 Villon begins the ubi sunt (where are . . . ?) theme that takes up a large part of the poem. In one highly lyrical and poignant passage he asks where all the young men he once knew have gone:

Ou sont les gracieux galans

Que je suivoye ou temps jadiz

Si bien chantans, si bien parlans,

Sy plaisans en faiz et en diz?

(Where are they, all the fine young men

I went about with formerly?

So good in song, so good in speech,

So pleasing in word and in deed?)

All will one day die; both rich and poor, “Mort saisit sans excepcion” (Death seizes them without exception). Two ballades continue the ubi sunt theme. In his 1533 edition Marot titled the first “La Ballade des dames du temps jadis” (The Ballade of the Ladies of Bygone Days) and the second “La Ballade des seigneurs du temps jadis” (The Ballade of the Lords of Bygone Days). In these two poems Villon asks what has become of the famous women and men of classical antiquity and the recent past. Where are Flora, Heloise, Blanche de Castille, and Joan of Arc? Where are Charlemagne, King Arthur, and Charles VII? One of Villon’s most celebrated ballades, “La Ballade des dames du temps jadis” ends with the poignant and much-quoted refrain “Mais ou sont les neiges d’anten?” (But where are the snows of yesteryear?).

Another recurring theme is that of unrequited love and women’s faithlessness and cruelty. In stanzas 46–56 Villon describes the lost beauty of an aged and ugly woman and then inserts a ballade Marot titles “La belle Heaulmiere aux filles de joie” (The Beautiful Helmet-Maker’s Wife Speaks to the Prostitutes), in which a once lovely and lustful woman gives advice to younger “working girls.” In stanza 63 Villon asks, “What drives women to love so freely and so many?” and answers “C’est nature femeninne” (It is feminine nature). In the double ballade that follows he advises men to avoid such women: “Bien eureux est qui rien n’y a!” (Happy the man who keeps away!).

After listing his personal misfortunes in love, he begins to bequeath his possessions. To his mother he leaves a ballade written in her own narrative voice: “Femme je suis povrecte et ancienne” (A woman I am, a poor and ancient one). In the dramatic monologue that follows, Villon’s mother addresses the Virgin and repeats the refrain: “En ceste foy je vueil vivre et mourir” (In this faith I desire to live and die). Villon also leaves ballades and other poems to his faithless lover, his friends, and his enemies. To Ythier Merchant—a possible love rival, according to Jean Dufournet—he leaves the poem that begins, “Mort j’appelle de ta rigueur” (Death, I appeal your harsh decree), challenging Merchant to set the poem to music. (It later appeared with musical accompaniment in two manus.) To others Villon leaves various real and imaginary possessions. Ironic asides and plays on words, the meaning of some of which can now only be surmised, abound, as do bitter attacks on his enemies. In one such attack he lists vile liquids and other substances as the ingredients for a recipe, ending with the refrain: “Soient frictes ces langues ennuyeuses!” (In all this may those spiteful tongues be fried!). Other ballades, such as the one Marot titles “Ballade de Villon et de la Grosse Margot” (Ballade of Villon and Fat Margot) are, as Barbara Nelson Sargent-Baur says, “deliberately coarse and disgusting.” Although they show a human side of Villon and are far from atypical of the period, these are not the poems for which he is best remembered.

The ballade that ends Le Testament is an example of the latter. In this poem Villon switches narrative voice again and writes in the third person, directly appealing to the reader as though the testator were already dead and, thus, the will can now be executed:

Icy se clost le testament

Et finist du povre Villon.

Venez a son enterrement,

Quant vous orrez le carillon

(Here closes and comes to an end

The testament of poor Villon.

Come to attend his burial

When you will hear the carillon).

Villon also alternates among the past, the present, and the future and between written and oral discourse.

The most studied and debated of Villon’s works, Le Testament has been characterized by Champion as “la plus pathetique des poesies” (the most moving of poems) as well as the most complex and ambiguous. Throughout the work Villon often changes not only his narrative voice but also his audience. Sargent-Baur studies Villon’s “multifarious audience” in her “Communication and Implied Audience(s) in Villon’s Testament” (1992) and finds that he addresses not only his friends and enemies but also an “ideal reader,” humanity in general, and himself or his “divided psyche.” In “Oral Textuality—Textual Orality: Patterns of Ambiguity in Francois Villon’s Testament” (1990) Robert D. Peckham says that Villon has created an ambiguity in the text by alternating between oral and written discourse. David Fein studies Villon’s use of time in his “Time and Timelessness in Villon’s Testament” (1987). All praise the work as the most complex and ambiguous of Villon’s oeuvre.

The sixteen works in Poemes varies were written at various times during Villon’s life, beginning around 1450; fifteen of them were published for the first time as a group in the 1892 edition of his works by Auguste Longnon. Most are ballades with three stanzas of eight to ten lines, each stanza ending with a refrain, and the whole ballade concluding with a short envoy with the same refrain. Three were included in Charles d’Orleans’s personal album. The first of these, written in praise of Marie d’Orleans, was written during Villon’s exile from Paris and ends “Vostre povre escolier Francoys” (Your poor scholar Francois). Villon apparently based the second, “Je meurs de seuf aupres de la fontaine” (I die of thirst at the fountain’s edge), on a theme proposed by the duke; the poem includes the name VILLON in acrostic. The third, written in macaronic style (in French and Latin), has been attributed to Villon but is unsigned. A fourth signed ballade was not included in the duke’s album but is an urgent request for a loan addressed to him.

Although most of the other works in Poemes varies include an acrostic of VILLON or FRANCOYS, it is not certain that Villon wrote all of them. The best known of the poems with an acrostic for his name, however, titled in most editions “Epitaphe” or “Epitaphe Villon” and commonly called “La Ballade des pendus” (The Ballade of the Hanged Men), is universally attributed to him. Apparently written in late 1462, when Villon was in the Chatelet prison under sentence of death, it is, perhaps, his most poignant poem. He adopts a collective narrative voice, writing from the point of

view of hanged men who urge their brothers to pray for them and to shun their example. He vividly describes the hanged men’s bodies swinging in the wind:

La pluye nous a debuez et lavez

Et le soulail deceschez et noirciz.

Pies, corbeaux nous ont les yeulx cavez

Et arache la barbe et les courcilz.

Jamais nul temps nous ne sommes assis;

Puis ca, puis la, comme le vent varie,

A son plaisir sans cess nous charie,

Plus becquetes d’oiseaux que dex a couldre.

(The rain has soaked us and has washed us clean

And the sun dried us up and turned us black.

Magpies and crows have hollowed out our eyes

And plucked away our beards and eyebrows too.

Never at any time are we at rest;

This way and that, as the wind may vary,

It pushes us about just as it likes,

More pecked by birds than any sewing thimble.)

Each stanza is followed by the haunting refrain “Mais priez Dieu que tous nous vueille absouldre” (But pray to God He may absolve us all).

Villon’s Ballades en jargon are written in the language of the Coquillards (thieves and counterfeiters). Critics have attempted to decipher these poems, but with limited success. The most complete study is Pierre Guiraud’s Le Jargon de Villon et le gai savoir de la Coquilwww.58yuanyou.comle (The Jargon of Villon and the Merry Learning of the Coquille, 1968). Most English translations of Villon’s work do not include Le Ballades en jargon, but Sargent-Baur has attempted an approximate translation of the poems in her Francois Villon: Complete Poems (1994).

One of the poems serves as an illustration of the type of poetry that Villon wrote in jargon as well as the debate on the meaning of the jargon poems. The first stanza reads:

Ioncheurs ionchans en ioncherie

Rebignez bien ou ioncherez

Quostac nembroue vostre arerie

Ou accolles sont voz ainsnez

Poussez de la quille et brouez

Car tost seriez rouppieux

Eschec quacollez ne soies

Par la poe du marieux.

Sargent-Baur translates the stanza:

Tricksters tricking in trickery,

Take a good look at where you play your tricks

Lest Ostac send your behind

Where your elders were taken by the neck.

Shake a leg and speed away

For you’d soon be sorry.

Take care not to let your neck be grabbed

By the hangman’s paw.

Sargent-Baur interprets this poem and other jargon poems as warnings to the Coquillards to watch out for the hangman, while Guiraud, who has translated the poem into modern French, refers to it as one of the “Ballades des tireurs de cartes” (Ballades of the Card Players) and sees it as advice to players who cheat. Interpretations and translations of the poems vary widely, and the debate promises to continue. While some have declared the poems hardly worth the effort to translate, others claim that they provide valuable insight into Middle French and the argot or slang of fifteenth- century France.

Villon used fixed forms, such as the ballade and the rondeau, even in the jargon poems. The stanza form he adopted for Le Lais and Le Testament is eight octosyllabic lines rhyming ababbcbc, which was used by Alain Chartier in La Belle Dame sans mercy (The Beautiful Lady without Mercy, 1424). The mock testamentary form was not new, either. Jean de Meun’s thirteenth-century Testament, Eustache Deschamps’s fourteenth-century Testament par esbatement, and Philippe de Hauteville’s early-fifteenth- century Confession et testament de l’amant trespasse de deuil (Confessions and Testament of the Lover Destroyed by Grief ) are earlier examples of the genre. Although Villon was not an innovator of forms or genres, the deeply personal nature of his poetry and his artistry ensure his place in the French literary canon, while the ambiguities inherent in his work and the resultant widely divergent interpretations ensure that his poetry will remain the subject of lively and continued critical debate.

搬运资料一小天,一口饭都没吃,炸酱面的干活